Statistics from 2019 indicate that approximately 301 million individuals were diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, and today, about 3.8% of the world’s population suffers from some form of anxiety. It is the most prevalent mental disorder among humans, yet it is also one of the most responsive to treatment.

Anxiety disorder affects the brain through a range of psychological symptoms such as tension, anger, and restlessness, as well as physical symptoms like heart palpitations, sweating, and trembling. It also limits the mind’s ability to concentrate, remember, and make decisions. Across its various types, anxiety disorder results from a complex mix of environmental, biological, and psychological factors.

——- Ad ——-

——- Ad ——-

How Does Anxiety Affect Your Brain?

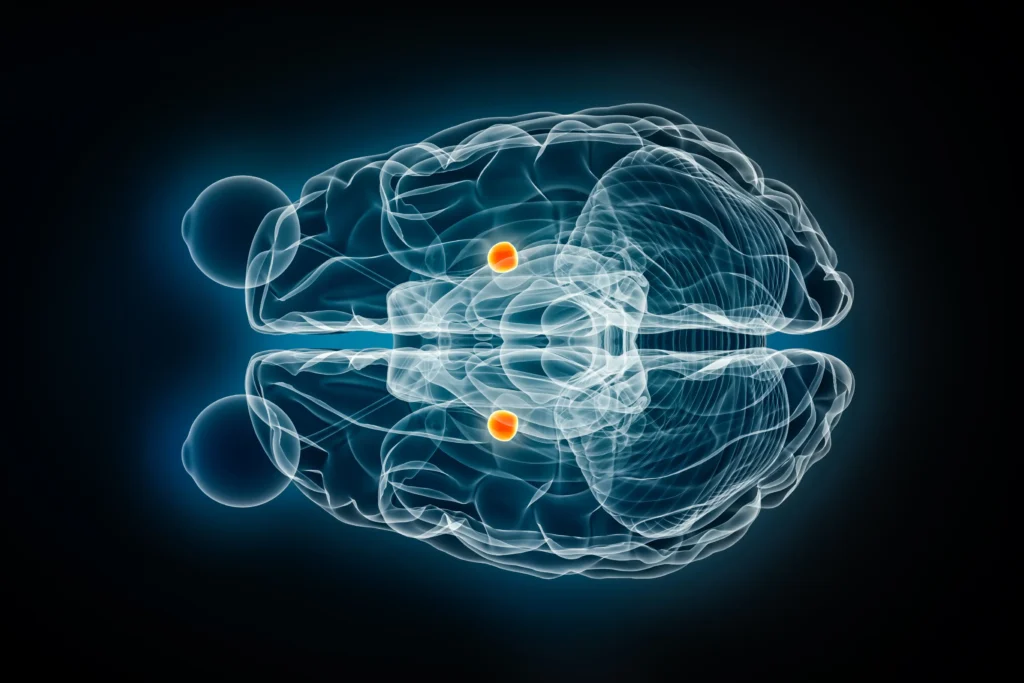

As mentioned, anxiety disorder impacts the brain, specifically affecting key cerebral regions. This effect is manifested by heightened activity in specific brain areas responsible for detecting threats and processing anxious feelings.

Consequently, it has been found that anxiety disrupts the balance of activity between the emotional centers, represented by the limbic system, and the cognitive centers of the brain, causing the emotional centers to become more active than usual.

This hyperactivity in emotional regions is paralleled by decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex, which plays a role in inhibiting threat responses. Below, we review the parts of the brain whose activity is altered by anxiety disorders and their role in the resulting symptoms:

1. Amygdala

Described as the brain’s fear and emotion center, its function is to analyze threats and negative emotions and to activate involuntary physiological responses like palpitations and sweating.

In this context, MRI studies have shown increased amygdala activity in patients with anxiety compared to healthy individuals. Due to this hyperactivity, a person feels fear and anxiety even in ordinary situations. Under the dominance of the overactive amygdala, the brain begins to interpret safe scenes as suspicious and anxiety-provoking, perpetuating continuous feelings of fear and anxiety in the patient.

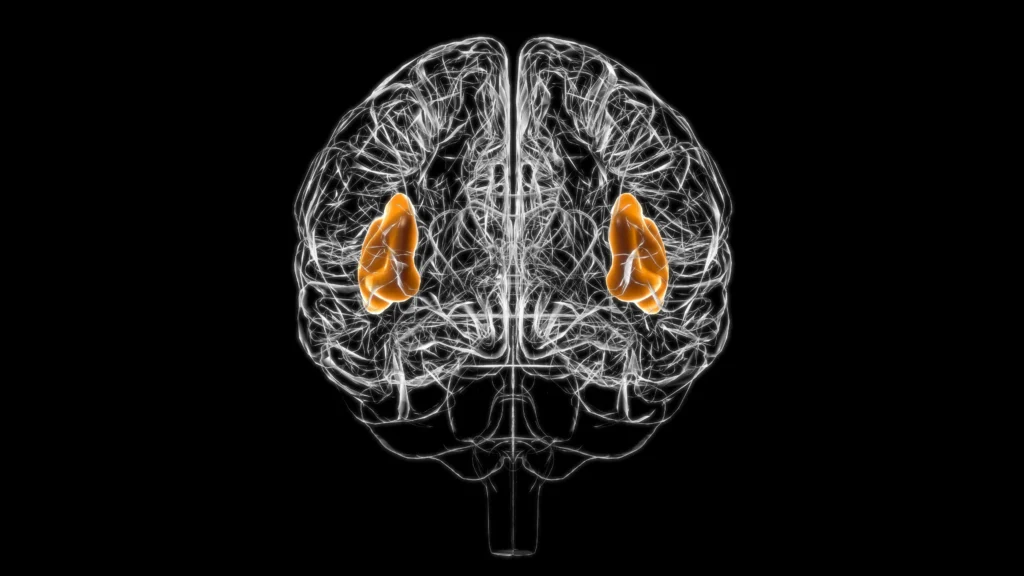

2. Insula

Also known as the insular cortex, it is located deep within the brain in the fissure separating the frontal and parietal lobes from the temporal lobe. Despite being hidden deep, its effect is evident in individuals with anxiety disorders.

The insular cortex performs numerous functions, including processing sensations, emotions, and even cognition, encompassing interoception (the internal sense of the body) and self-awareness of one’s own emotional state.

This region becomes active when evaluating feelings and searching for bodily signals that suggest a threat, such as palpitations and trembling. Consequently, it has been found that the brains of individuals with anxiety show heightened insula activity. This leads to the magnification and exaggeration of physical signals like heart rate, pressure on the chest, and rapid breathing, which in turn exacerbates feelings of tension and agitation.

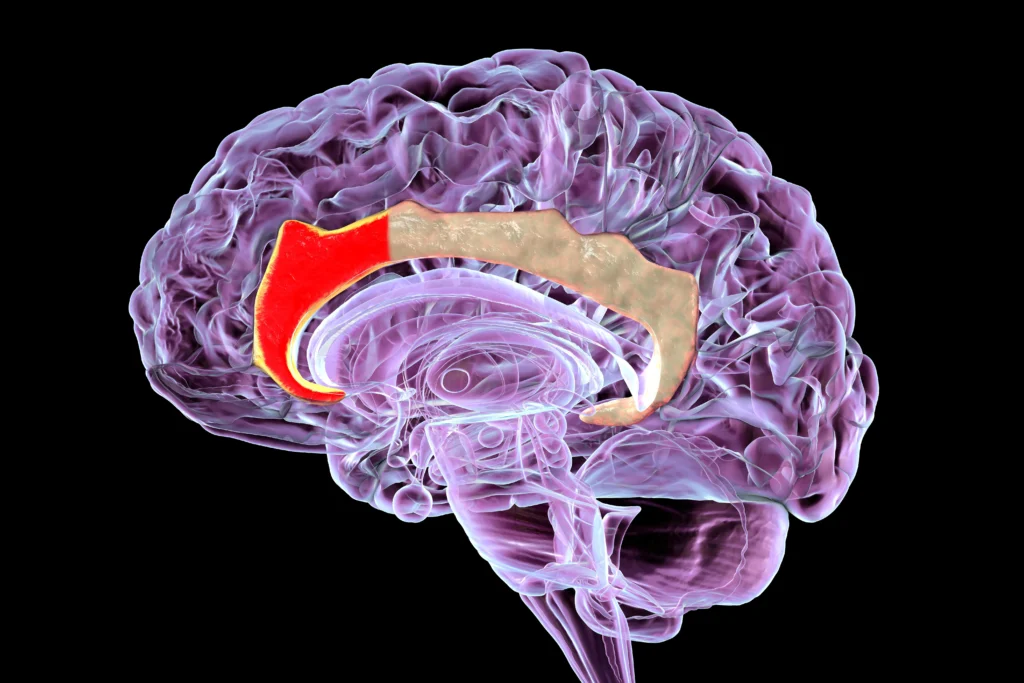

3. Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC)

This is the front part of the cingulate gyrus and plays a role in speech, emotional response, and the perception of pain. Its activity increases when a person faces anticipated fears or threats. According to studies, ACC activity is elevated in individuals with anxiety.

As a result of this increase, the brains of anxiety patients suffer from intense focus on risks and excessive monitoring and rumination on negative thoughts, which raises tension levels and deprives the person of relaxation and mental peace.

4. Prefrontal Cortex (PFC)

Unlike the previous regions, the prefrontal cortex shows less activity in individuals with anxiety disorders. It is responsible for conscious thought and emotional control, and it exerts inhibitory functions over the hyperactivity of parts of the limbic system, such as the amygdala.

Therefore, the ability of anxiety patients to control their worries and maintain composure during stressful situations is diminished due to the dominance of fear centers like the amygdala and insula, which corresponds to reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex.

5. Hypothalamus and Locus Coeruleus

Known as stress response centers, the brain uses them for the early processing of anxiety-inducing factors. Each region has a distinct role: the Hypothalamus regulates the secretion of stress hormones like cortisol, while the Locus Coeruleus specializes in producing noradrenaline, which is involved in regulating attention and alertness and operates as part of the fight-or-flight response.

These two areas are activated as soon as a person is exposed to a stressful situation, and their activity is amplified, leading to symptoms such as a rapid heartbeat, sweating, and muscle contractions, which further increase the individual’s levels of anxiety and stress.

——- Ad ——-

——- Ad ——-

How Does Increased Brain Activity Contribute to Anxiety Symptoms?

According to neurological research conducted in 2018 using MRI, it was found that the greater the activity in the brain’s emotional regions, the higher the emotional sensitivities and reactive responses to dangers or threats, even in safe or normal situations devoid of any actual risk.

In the case of the amygdala and the insular cortex, increased activity in these two areas leads to the characterization of neutral stimuli as threatening, and the brain responds with exaggerated fear and a persistent sense of threat.

These feelings of fear and anxiety take hold within the patient amidst the subdued activity of the frontal lobes, which are responsible for curbing intense emotions. Consequently, stress takes control of the patient as the activation of these emotional centers in the brain increases.

Methods to Reduce Hyperactivity in Brain Regions Linked to Anxiety

Several methods are available for individuals with anxiety to reduce the heightened activity in the brain’s emotional centers, as follows:

1. Natural Approaches

● Mindfulness Meditation: Recent studies have proven that practicing mindfulness meditation reduces the size and reactivity of the amygdala to anxiety-provoking stimuli, thereby diminishing agitated and disturbed reactions.

Meditation also increases the activity of the prefrontal cortex and its communication with the cingulate gyrus, enhancing cognitive control over emotions. According to another study, following an 8-week meditation program like MBSR (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction) led to an increase in the thickness of the right insular cortex, associated with interoception, along with a decrease in anxiety and stress levels among participants.

These changes indicate the effectiveness of mindfulness meditation in rebalancing neural circuits in the brain, weakening amygdala activity while boosting the efficacy of the prefrontal cortex.

● Deep Breathing Exercises: Slow, regular breathing increases the activity of the parasympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the body’s rest and relaxation response, and it inhibits the heightened sympathetic nervous system activity that leads to stress and anxiety.

Evidence has shown that increasing the duration of breaths (long inhales and exhales) lowers heart rate and activates the parasympathetic system, reducing stress and negative feelings.

Evidence also suggests that breathing techniques induce neurological changes in the brain’s attention and alert networks, affecting areas like the amygdala, insula, and anterior cingulate cortex, which are associated with emotion processing.

● Physical Activity: Regular exercise builds the brain’s resilience against stress and anxiety. Research has shown that physical activities like running and walking enhance the functional connectivity between the amygdala and cortical control regions.

In this vein, a 2019 study on healthy volunteers demonstrated that exercise strengthens the amygdala’s neural communication with reward and relaxation centers like the orbitofrontal cortex and the insular cortex, thereby neutralizing its influence within fear centers.

Furthermore, a recent study found that walking for one hour in a natural environment, such as a forest or plain, reduces amygdala activity compared to walking in a city or a noisy environment.

● Yoga: Yoga combines the three preceding methods (meditation, deep breathing, and physical activity) into a single discipline, offering multiple benefits and better results. Research has found that yoga practitioners exhibit superior abilities in cognitively controlling negative emotions.

In mental tests where participants faced negative stimuli, yoga practitioners relied more on their prefrontal cortex to manage their emotions, with a simultaneous suppression of amygdala activity. A positive correlation was also observed between the number of weekly yoga sessions and an improvement in the thickness of the anterior cingulate cortex (involved in attention focus and emotion regulation).

In other words, yoga helps train the brain to disengage from processing negative information and, instead, to engage the brain’s functions related to thinking and concentration.

2. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

As one of the oldest psychological methods for treating anxiety and stress, neuroimaging research has concluded that it has a clear effect on the brain. Confirming this, fMRI experiments revealed that patients who underwent CBT sessions experienced a significant increase in the activity of prefrontal regions (ventromedial and dorsolateral PFC) dedicated to cognitive control and emotion regulation, alongside a marked decrease in amygdala activity and excessive emotional symptoms.

Simultaneously, all the natural methods mentioned above fall under the CBT approach, among other techniques. However, CBT involves a very deep dive into each patient’s case and the patterns affecting their feelings and behavior, which are then systematically, professionally, and thoughtfully modified.

To this end, a CBT therapist guides the patient through a large number of sequential steps to treat anxiety and stress. These steps begin with identifying the patient’s thoughts and the negative circumstances in their life and gradually progress to training the patient to confront and manage their fears.

3. Medical Interventions

These are methods utilized under medical supervision, as follows:

● Medications

Antidepressants such as Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and other drugs are used to treat anxiety disorders, in addition to tranquilizers like benzodiazepines. These medications have a direct effect on the brain regions responsible for anxiety.

One study found that individuals on SSRIs showed reduced amygdala activity in response to negative stimuli and increased activity in response to positive stimuli. This is attributed to the ability of these drugs to modulate serotonin in the brain, which helps regulate mood and activate the prefrontal cortex. As for benzodiazepines, they activate GABA receptors in the amygdala, and imaging studies have confirmed that they immediately reduce amygdala activity.

Additionally, short-term SSRI use has been found to decrease activity in the insular and anterior cingulate cortices during the brain’s anticipation of unpleasant situations. In short, these medications work to restore chemical balance in the brain, counteracting the excessive effect of anxiety in the amygdala and activating the cortical cognitive regions that contribute to emotion regulation.

● Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

This is a non-invasive technique that uses magnetic pulses to stimulate specific cortical areas. It is commonly used for depression, and its research has expanded to include anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), given that these disorders are characterized by hyperactivity in the amygdala.

According to research where TMS pulses were applied to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a tangible change in the level of amygdala activity was observed; the magnetic stimulation leads to a reduction in any increase in the amygdala’s activity.

——- Ad ——-

——- Ad ——-

Conclusion

It is worth noting that every case of anxiety can have a happy ending, which can be achieved once it is subjected to appropriate and prompt treatment. The journey to recovery begins with the patient—and the doctor—understanding the nature of anxiety’s impact on their brain and body and the specific brain regions affected.

This self-awareness helps patients respond to the illness and learn how to confront and manage its symptoms. If you have experienced any signs of anxiety, take the initiative to consult a specialized doctor to evaluate your condition and provide you with a comprehensive and effective treatment plan.

○ Share the article:

References

(1) Madonna, D., Delvecchio, G., Soares, J. C., & Brambilla, P. (2019). Structural and functional neuroimaging studies in generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil : 1999), 41(4), 336–362.

(2) Langhammer, T., Hilbert, K., Adolph, D., Arolt, V., Bischoff, S., Böhnlein, J., Cwik, J. C., Dannlowski, U., Deckert, J., Domschke, K., Evens, R., Fydrich, T., Gathmann, B., Hamm, A. O., Heinig, I., Herrmann, M. J., Hollandt, M., Junghoefer, M., Kircher, T., Koelkebeck, K., … Lueken, U. (2025). Resting-state functional connectivity in anxiety disorders: a multicenter fMRI study. Molecular psychiatry, 30(4), 1548–1557.

(3) Schimmelpfennig, J., Topczewski, J., Zajkowski, W., & Jankowiak-Siuda, K. (2023). The role of the salience network in cognitive and affective deficits. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 17, 1133367.

(4) Calderone, A., Latella, D., Impellizzeri, F., de Pasquale, P., Famà, F., Quartarone, A., & Calabrò, R. S. (2024). Neurobiological Changes Induced by Mindfulness and Meditation: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines, 12(11), 2613.

(5) Luo, Q., Li, X., Zhao, J. et al. The effect of slow breathing in regulating anxiety. Sci Rep 15, 8417 (2025).

(6) Chen, YC., Chen, C., Martínez, R.M. et al. Habitual physical activity mediates the acute exercise-induced modulation of anxiety-related amygdala functional connectivity. Sci Rep 9, 19787 (2019).

(7) Gothe, N. P., Khan, I., Hayes, J., Erlenbach, E., & Damoiseaux, J. S. (2019). Yoga Effects on Brain Health: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature. Brain plasticity (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 5(1), 105–122.

(8) Young, K. D., Friedman, E. S., Collier, A., Berman, S. R., Feldmiller, J., Haggerty, A. E., Thase, M. E., & Siegle, G. J. (2020). Response to SSRI intervention and amygdala activity during self-referential processing in major depressive disorder. NeuroImage. Clinical, 28, 102388.

(9) Korn, C. W., Vunder, J., Miró, J., Fuentemilla, L., Hurlemann, R., & Bach, D. R. (2017). Amygdala Lesions Reduce Anxiety-like Behavior in a Human Benzodiazepine-Sensitive Approach-Avoidance Conflict Test. Biological psychiatry, 82(7), 522–531.

(10) Sydnor, V. J., Cieslak, M., Duprat, R., Deluisi, J., Flounders, M. W., Long, H., Scully, M., Balderston, N. L., Sheline, Y. I., Bassett, D. S., Satterthwaite, T. D., & Oathes, D. J. (2022). Cortical-subcortical structural connections support transcranial magnetic stimulation engagement of the amygdala. Science advances, 8(25), eabn5803.